FUNDAMENTALS OF INTERFACIAL SCIENCE

This brief introduction into interfacial phenomena is thought to help users of interfacial measuring technique to better understand what instrument is most suitable for a certain problem, and which possibilities do exist to understand the measured data.

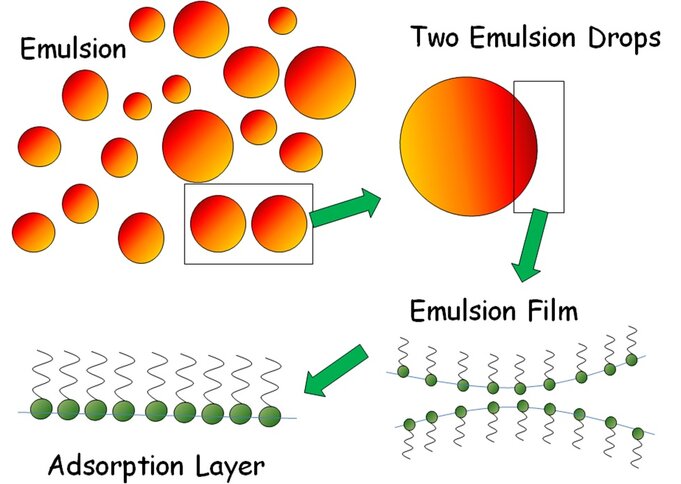

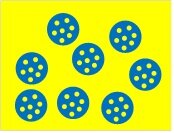

There are many motivations for interfacial studies. Many applications are based on foams or emulsions. As an example the principle features of an emulsion system are shown in the following schematic.

An emulsion consists of a huge number of drops of different size interacting with each other. When two drops contact each other a liquid film is formed which is stabilized by adsorbed molecules, here symbolized by adsorbed surfactants. The film is built up by two adsorption layers. Hence, the properties of these adsorption layers, also subjected to deformations like compression and expansion or shear, is of essential importance for understanding the formation and stabilisation of emulsions. The situation with foams has a lot in common with emulsions and similar problems arise.

Adsorption of surfactants

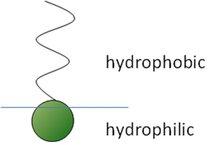

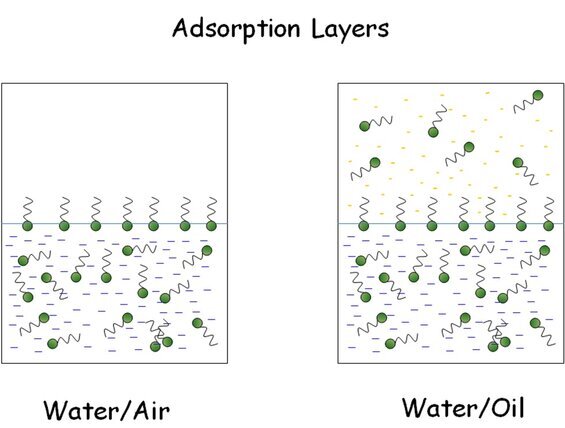

Surfactants are molecules with a so-called amphiphilic character, i.e. they consist of a hydrophilic part and a hydrophobic part. While the hydrophilic headgroup prefers to be located in water, the hydrophobic tail prefers to be in air or oil, which makes the interface an ideal location for such amphiphilic molecules.

Key parameters of adsorption layers are the dynamics of adsorption during their formation, the equilibrium parameters of adsorption, and the rheological behaviour, including the elasticity and viscosity of dilation and shear (in a broad frequency interval). At the interface between two immiscible liquid, such as water and oil, molecules adsorb and partly pass into the oil phase. The distribution of the surfactant between the two phases is given by the distribution coefficient.

Adsorption of polymers

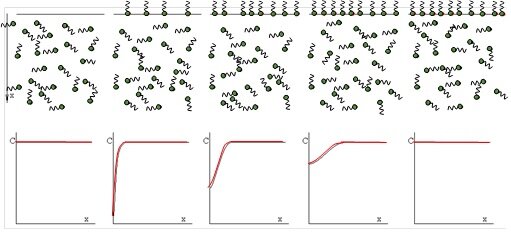

Also polymers, in particular protein, are surface active. As example the process of adsorption of a protein at the water-air interface is shown here. The protein is transported in the solution bulk by diffusion, arrives at the surface and adsorbs, and at the interface it is changing its conformation. The extent of this unfolding and denaturation process depends on the space available at the interface.

Also polymers, in particular protein, are surface active. As example the process of adsorption of a protein at the water-air interface is shown here. The protein is transported in the solution bulk by diffusion, arrives at the surface and adsorbs, and at the interface it is changing its conformation. The extent of this unfolding and denaturation process depends on the space available at the interface.

Adsorption Isotherms

The surface activity of a surfactant or protein is best documented by the so-called adsorption isotherm. This isotherm represents the relationship between the bulk concentration c and the surface excess Γ (adsorption) at the interface. The most simple relationship is the linear Henry isotherm:

The most frequently used isotherm, however, is the Langmuir isotherm, which contains two physical parameters, a characteristic concentration a at which half of the interface is covered by the surfactant, and the maximum amount that can be adsorbed Γ∞:

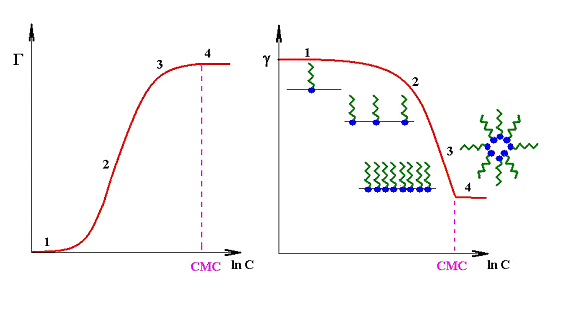

The following schematic shows how Γ is changing with increasing concentration c in the solution bulk.

When a certain bulk concentration of the surfactant is reached and the surface is completely covered so that no further molecules can be adsorbed at the interface, further surfactant molecules form aggregates in the solution bulk, micelles. At this so-called critical micelle concentration CMC, Γ becomes essentially constant, and also the surface tension gamma shows a kink and remains almost constant above the CMC.

Methods for measuring equilibrium adsorption

Ellipsometry is a possibility to measure directly the adsorption of surfactants at liquid interfaces. For pros and cons and range of applicability, please look into literature (H. Motschmann and R.Teppner, Ellipsometry, in “Novel Methods to Study Interfacial Layers”, Studies in Interface Science, Vol. 11, D. Möbius and R. Miller (Eds.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2001, p. 1). Easier accessible is the surface tension of a solution. Via thermodynamic models it is possible to determine the adsorbed amount from so-called surface tension – concentration isotherms g(c). The equivalent to the above Langmuir isotherm is the von Szyszkowski isotherm:

go is here the surface tension of the pure solvent, and R and T are the gas low constant and the absolute temperature.

The classical isotherms, for example Langmuir and also the more advances Frumkin isotherms, do not describe perfectly all experimental data. In recent time, better models have been developed, which are summarised in a book (V.B. Fainerman, D. Möbius and R. Miller (Eds.), Surfactants – Chemistry, Interfacial Properties and Application, in Studies in Interface Science, Vol. 13, Elsevier, 2001 ). As an example, the following graph shows the surface tension isotherms of five members of the homologous series of fatty acids, a classical model surfactant.

Kinetics of adsorption

The adsorption process of surface active molecules at interfaces is a time process. When a fresh interface is formed, no molecules are adsorbed. Those close to the interface can adsorb first, creating a concentration gradient in the layer adjacent to the interface. Due to diffusion molecules move and re-establish a homogeneous distribution in the solution bulk. The schematic below shows the steps of such an adsorption process.

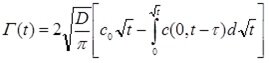

The graphs demonstrate how the concentration gradient towards the surface first increases and then decreases with time and leads finally again to a homogeneous surfactant distribution in the solution bulk. The theoretical model which describes the "diffusion controlled" adsorption process of surfactants at a solution surface was derived by Ward & Tordai in 1946 and results in a Volterra-type integral equation:

where D is the diffusion coefficient and co is the surfactant bulk concentration. The equation describes the change of Γ(t) with time t, however, its application to dynamic surface tension data g(t) is not simple. In the book mentioned above by Fainerman, Möbius and Miller a paragraphs is dedicated to the general physical idea of all adsorption kinetics models, and to particularities of various models.

Dynamic surface tension with overlapping time intervals

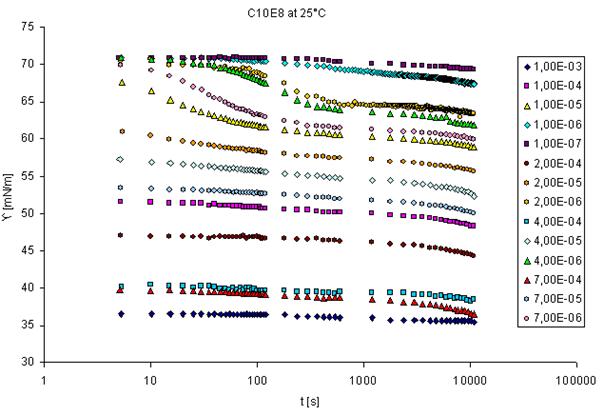

The adsorption dynamics is best studied by measuring the dynamic surface tension, or in case of interfaces between two immiscible liquids the dynamic interfacial tension. There are various methods available for such measurements having different time windows. Methods with complementary time windows are needed, even for the study of one surfactant, as the rate of adsorption depends on its surface activity and the concentration in the solution bulk. This is best seen from the following graph which shows the dynamic surface tension measured with a drop shape technique (see PAT-1M and PAT-2S, products of SINTERFACE).

This method yields values for very long adsorption times (here up to about 10.000 s) however, for short times no data are provided by this technique. For a concentration up to 7×10-6 mol/l this time interval seems to be sufficient, for higher concentrations, however, the surface tensions at 5 seconds (the lowest time measured by the PAT-1M here, actually it can start from about 1 s), are significantly lowered due to adsorption. For such surfactant concentrations measurements at much shorter adsorption times are required. The only technique that provides data at adsorption times down to 1 ms and even less is the bubble pressure tensiometry (see BPA-1S and BPA-2S from SINTERFACE). For dynamic interfacial tensions short adsorption times like 1 ms are not accessible by any existing method. The following schematic gives an overview of existing methods for dynamic surface and interfacial tensions and the corresponding time windows. The drop pressure module (DPA-1 and ODBA-1) is the first experimental set-up which allows to measure at short adsorption times. Depending on experimental details, times even below 10 ms could be accessible.

The choice of a suitable method is sometimes not so easy, as for certain problems many methods exist, and all of them have advantages against others, in respect to easy handling, available temperature control, applicability to liquid-gas and liquid-liquid interfaces etc. What however, becomes evident as well is, that there is no method that covers the whole range of time and needs. Note, for highly concentrated solutions, i.e. for most surfactant solutions above the CMC, even 100 μs appear to be a long adsorption time. An actual summary of experimental possibilities using drop and bubble methods and an excellent selection of experimental examples has been published recently (R. Miller and L. Liggieri (Eds.), Bubble and Drop Interfaces, in “Progress in Colloid and Interface Science”, Vol. 2, Brill Publ., Leiden, 2011, ISBN 978 90 04 17495 5).

2D Rheology - general idea

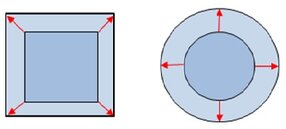

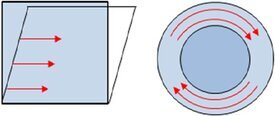

When interfacial layers are deformed there are forces acting against this deformation. There are principally two forms of deformation:

- shear deformation: changing shape of the interface at constant area

- dilational deformation: constant shape but changing surface area.

The possibility of expansion and compression of an interfacial layer is a peculiarity different to bulk rheology, where in a first approach incompressible liquids are assumed.

Expansion or compression deformation

Shear deformation

Both types of deformation provide one elasticity and one viscosity parameter, each.

A first complete book on interfacial rheology was published recently (R. Miller and L. Liggieri (Eds.), Interfacial Rheology, Vol. 1, Progress in Colloid and Interface Science, Brill Publ., Leiden, 2009, p. 567-613, ISBN 978 90 04 17586 0).

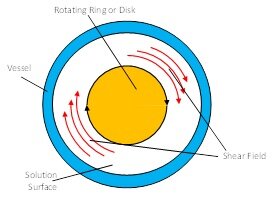

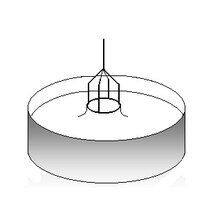

For surface layers the general set-up of the shear rheometer ISR-1 is shown in the schematic below. On the right side a special biconical disk is shown which is used for experiments at liquid-liquid interfaces.

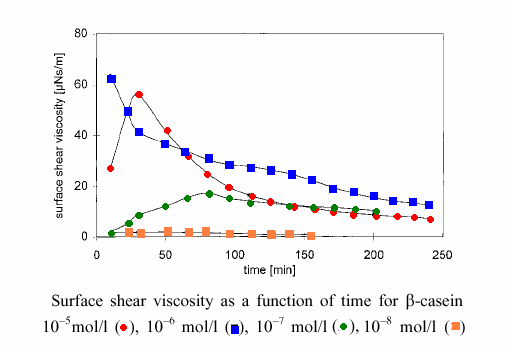

The surface shear viscosity of ß-casein is shown in the following figure. Depending on the bulk concentration, the shear viscosity increases and then drops down again.

This behaviour can be explained by the structure of the interfacial layer formed by the

β-casein molecules, which is more cross-linked at lower surface coverage with more unfolded protein molecules, and less cross-linked at higher surface coverage.

Dilational rheology

For the dilational rheology the parameter E0 is defined as the dilational elasticity module

This parameter results directly from the interfacial thermodynamics. Using for example the Langmuir isotherm (see above) we obtain the following relationship

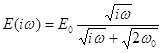

When harmonic perturbations are imposed to an interfacial layer an oscillation behaviour of the interfacial tension is observed. This behaviour can be described by the complex elasticity E(iω) defined by the following equation

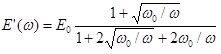

For a diffusion controlled exchange of matter we obtain

where the real and imaginary parts are given by

Experiments are performed to measure the frequency f dependence of E' and E" in order to find the characteristic relaxation frequencies of an interfacial layer. Here,  and

and  is the diffusion relaxation time.

is the diffusion relaxation time.

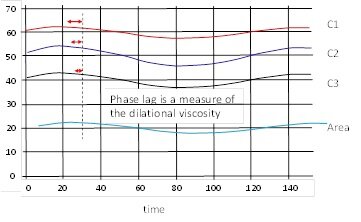

A typical dilational experiment can be carried out with the drop shape tensiometer PAT.

Using the dosing system the drop area can be subjected to transient or harmonic perturbations, such as those shown in the following graph: after 3 h keeping the drop surface area constant (10800 s) first 3 square pulses are performed, and then 3 oscillations each at 2 frequencies.

From such experiments we can determine the dilation elasticity and viscosity. The phase lag between g(t) and the area change is a measure of the dilational viscosity.

On the other hand, the amplitude of g(t) is a measure of the elasticity at the given frequency.

With increasing bulk concentration the elasticity E' increases and passes through a maximum. The same happens with the viscous term E", as one can see in the following graph showing results for a model surfactant (dodecyl dimethyl phosphine oxide) at a frequency of 0.3 rad/s = 0.048 Hz.

The measured dilational rheology is a function of frequency and only at very high oscillation rates a plateau value is reached, which theoretically should coincide with the value of E0 obtained from the adsorption isotherm.

Foams and emulsions

For the characterization of emulsions, essentially the evolution of drop size distribution with time includes all important information. Unfortunately, there is no commercial instrument that allows a general study of this behaviour. Main problem is the automation of such an analysis and the interference of sedimentation/creaming processes.

For foams the situation is quite different, as there are various commercial instruments on the market. Most of them are based on the procedure proposed by Ross and Miles, i.e. on the measurement of the breakdown of a foam column to half of its height. Some instruments also measure the drainage as function of time, however, mainly under not well defined conditions. The Foam Analyzer FA-1 produced by SINTERFACE is the first instrument that allows to determine drainage and stability of a foam under standardized conditions, i.e. as a function of applied partial vacuum. This provides the possibility of a quantitative correlation between foam and foam film properties and gives access to a deeper understanding of processes stabilizing and destabilizing foams.

The new tool DBMM, the Drop Bubble Micro Manipulator, represents a unique opportunity to mimic the situation in foams and emulsions. Two bubbles or drops can be formed at the tip of a capillary, each, and then manipulated against each other, as it is the case in real liquid disperse systems. Even the asymmetric case of a bubble and a drop can be created (see also R. Miller and L. Liggieri (Eds.), Bubble and Drop Interfaces, in “Progress in Colloid and Interface Science”, Vol. 2, Brill Publ., Leiden, 2011, ISBN 978 90 04 17495 5).

The same tool with small modifications can be also used to study elementary processes in multiple emulsions, where for example water drops are dispersed in a oil matrix, while inside these water drops oil droplets are dispersed. This type is called oil-in-water-in oil double emulsion (o/w/o).

The DBMM would then be equipped with a special double capillary in order to provide the situation of a drop formed inside a drop which in turn is immersed into another liquid, which could be the same oil like the internal dispersed phase.

METHODS

General Information

Methods for surface and interfacial tension measurements

Each material has a specific surface energy equivalent to the surface tension. This quantity is equal to the energy needed to create a new surface of a unit area. While liquids such as alkanes have quite a low surface tension, more polar liquids exhibit much higher tensions. The situation with solid materials is similar: there are those with low and with high surface tension. The tensions between two condensed materials are typically much smaller and can even approach values near zero which leads to fascinating phenomena. This is for example the case when oil is brought into contact with an aqueous surfactant solutions. When the interfacial tension (the tension between the two liquids) is close to zero a spontaneous emulsification is observed and no mechanical energy is needed to disperse one phase into the other [[i]]. Another example is the process of wet grinding. While large input of energy would be required to grind a number of materials in air, the energy input for grinding suspended in a liquid can be orders of magnitude lower (Rehbinder effect, see [[ii]]). There is quite a number of methods for measuring the surface tension of a liquid or the interfacial tension between two immiscible liquids. Table 1 gives an overview of methods dedicated to surface tension measurements of liquid interfaces. As one can see, most of these methods are based on concepts with single drops or bubbles, as it was extensively described in a recently published book (R. Miller and L. Liggieri (Eds.),Bubble and Drop Interfaces, Vol. 2, Progress in Colloid and Interface Science, Brill Publ., Leiden, 2011, p. 195-222; ISBN 978 90 04 17495 5).

Table 1: Methods for measuring surface and interfacial tension of liquid interfaces; according to [3]

Method | Suitability for Liquid/Liquid | Suitability for Liquid/Gas | Commercial Set-up available | ||||

Capillary Rise Technique | possible | good | no | ||||

Capillary Wave Damping | possible | good | no | ||||

Drop Volume Method | good | good | yes | ||||

Growing Drops and Bubbles | good | good | no | ||||

Inclined Plate Method | bad | good | no | ||||

Maximum Bubble Pressure Method | bad | good | yes | ||||

Oscillating Jet | bad | good | no | ||||

Pendent Drop Method | good | good | yes | ||||

Plate Tensiometry | possible | good | yes | ||||

Ring Tensiometry | possible | good | yes | ||||

Sessile Drop Method | possible | possible | yes | ||||

Spinning Drop Technique | good | possible | yes | ||||

Static Drop Volume Method | good | good | available |

Some methods are based on dynamic principles and are thus suitable to measure the tension as a function of time. Others are static or quasi-static methods and yield dynamic tensions as well but also allow to approach the equilibrium state of a liquid interface and hence are able to measure the equilibrium tension. While dynamic methods require theories for data interpretation that take the dynamic character into consideration, the data from static methods can be understood more easily. To overcome this problem Joos developed a theory which reduces the data from dynamic methods to a so-called effective lifetime of the interface, which is equivalent to the time needed at a static interface to reach the adsorption state [[i]]. In this way measurement results from all experimental techniques can be directly compared. Each of the given methods has advantages and drawbacks. Actually, none of these methods can provide all the possibilities needed in practice and only a proper selected number of measuring techniques can satisfy the requirements in a surface science laboratory. The most important criterion for users is certainly the availability of commercial set-ups which is particularly marked in the Table 1. Using interfacial methods one comes across the problem of sample purity. Small amounts of surface active components in a liquid can cause dramatic changes in the surface tension. Thus, the correct functioning of a method cannot be simply obtained by measuring an arbitrary liquid. It is rather recommended for such test measurements to use a liquid system with well-known properties and high purity. When the respective measuring value for the chosen standard sample is reached within a certain limit of accuracy, the user can conclude about the functioning of the instrument as well as the quality of the samples. There are few samples useful for such test measurements only. Table 2 provides important data for a number of such liquids. These values are confirmed by various authors and methods and can serve as standard.

Table 2: Surface tension and density of some standard liquids

Liquid | °C | g/cm³ | mPa s | mN/m | |||||

Water | 15 20 21 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 | 0.9991 0.9982 0.9980 0.9971 0.9957 0.9940 0.9923 0.990 0.988 0.986 0.98 | 1.002 0.890 0.798 0.653 0.547 0.467 | 73.5 72.75 72.6 72.0 71.2 70.5 69.6 68.9 68.0 66.9 66.2 | |||||

Hexane | 20 | 0.660 | 0.326 | 18.4 | |||||

Heptane | 20 | 0.684 | 0.409 | 19.7 | |||||

Octane | 20 | 0.703 | 0.542 | 21.6 | |||||

Nonane | 20 | 0.718 | 0.711 | 22.9 | |||||

Decane | 20 | 0.730 | 0.92 | 23.9 | |||||

Dodecane | 20 | 0.751 | 1.35 | 25.4 | |||||

Tetradecane | 20 | 26.7 | |||||||

Hexadecane | 20 | 0.7733 | 27.6 | ||||||

Ethylen Glycol | 21 | 47.7 | |||||||

Methanol | 21 | 22.3 | |||||||

Ethanol | 20 | 0.789 | 22.0 | ||||||

Hexanol | 20 | 0.814 | 25.8 | ||||||

Octanol | 20 | 0.827 | 27.5 | ||||||

Decanol | 20 | 0.830 | |||||||

Benzene | 20 | 0.877 | 0.652 | 28.9 | |||||

Chloroform | 15 | 1.489 | 27.2 | ||||||

Toluen | 20 | 0.867 | 0.59 | 28.5 | |||||

Dioxane | 20 | 1.034 | 35.4 |

Note, that in general the interface between two liquids is affected by surface active impurities most strongly, and the interfacial tension measured is not a reliable value. This even holds although the surface tensions of the two liquids used have correct values. Besides the correct surface tension value for a liquid as criterion of purity, there should also be no change of g with time. This behaviour should be tested over the time interval of interest. In Table 3 values are given for the interfacial tension between two liquids, both mutually saturated in order to avoid effects caused by the matter transfer across the interface. Note, that all liquids have a certain solubility in a second liquid. The solubility limits at room temperature are also given in Table 3.

Table 3: Interfacial tensions g between water and a second liquid and mutual solubility

Substance | °C | Solubility in Water, mol-% | Solubility of Water, mol-% | mN/m | |||||

Hexane | 20 | 3x10-4 | 0.043 | 51.0 | |||||

Heptane | 20 | 5x10-5 | 0.070 | 51.2 | |||||

Octane | 20 | 1x10-5 | 0.060 | 51.3 | |||||

Decane | 20 | 2x10-7 | 0.057 | 51.8 | |||||

Dodecane | 20 | 4x10-8 | 0.061 | 52.1 | |||||

Tetradecane | 20 | good | 52.4 | ||||||

Chloroform | 15 | 0.15 | 0.517 | 36.1 | |||||

Hexanol | 20 | 0.1 | 29.0 | 6.8 | |||||

Octanol | 20 | 0.06 | 19.4 | 8.5 | |||||

Benzene | 20 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 35.0 | |||||

Toluene | 20 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 36.1 |

For many liquid systems the interfacial rheology yields very important information. Thus, the stability of foams or emulsions is mainly controlled by the elasticity and viscosity of the interfaces [[i]]. Interfacial layers of surfactants or polymers are able to change the mechanical behaviour of liquid interfaces strongly. In contrast to bulk rheology, where essentially the shear rheology is of importance, interfaces have a remarkable dilational rheology [[ii]]. The response to transient and harmonic perturbations can be used to determine the two quantities dilational elasticity and viscosity. There are few methods available only for studies of the interfacial rheology. Most of these methods do exist as laboratory set-ups but commercial instruments are not on the market. In Table 4 some of the techniques used for interfacial rheological studies are summarized. As one can see, the drop and bubble shape method allow measurements of the dilational rheology of interfacial layers, at liquid/gas as well as liquid/liquid interfaces. The software of PAT1 offers particular time functions for such studies as will be demonstrated further below.

Table 4: Methods for measuring surface and interfacial rheology of liquid interfaces; according to [[iii]]

Method | Suitability for Liquid/Liquid | Suitability for Liquid/Gas | Commercial Set-up available | ||||

Interfacial Shear Methods | |||||||

Torsion Shear Rheometry | possible | good | yes | ||||

Canal Surface Vescosimeter | impossible | possible | no | ||||

Deep Channel Surface Viscosimeter | impossible | possible | no | ||||

Interfacial Dilation Methods | |||||||

Capillary Wave Damping | possible | good | no | ||||

Longitudinal Wave Damping | possible | good | no | ||||

Oscillating Drops and Bubbles | good | good | yes | ||||

Drop and Bubble Shape | good | good | yes | ||||

Elastic Ring Method | impossible | possible | no | ||||

Oscillating Cylinder Method | impossible | possible | no |

For studies on solid surfaces, no direct methods for measuring the surface tension exist and indirect procedures must be applied. Most common are combined contact angle and surface tension measurements. Other techniques have been described, for example, by Rusanov and Prokhorov [[i]]. The surface energy of a solid can be calculated from the contact angle and the respective surface tension of the used liquid by applying a respective theory. For users intending to determine the surface energy of solids it seems interesting to have again some reference values. This, however, is not so trivial like for liquids. The reason is that solid material cannot be provided in a standard form like it is the case for liquids and the surface properties can therefore vary from sample to sample (cf. Table 5).

Table 5: Contact angle and surface energy of some selected liquids, according to [[ii]]

| Liquid | Solid | °C | mN/m | Contact Angle ° | |||||

| Water | Oilysterene | 22 | 47.0 | 60.0 | |||||

Water | PTFE | 20 | 20.0 | 104.0 | |||||

Water | Polyethylene | 20 | 30.3 | 87.1 | |||||

Water | PETP | 20 | 35.8 | 79.1 | |||||

Diethylen Glycol | PETP | 20 | 35.6 | 41.2 | |||||

Ethylen Glycol | PETP | 20 | 35.1 | 47.5 | |||||

Formamid | PETP | 0.15 | 35.4 | 61.5 | |||||

Glycerol | PETP | 20 | 35.5 | 68.1 |

Ring and Plate

Ring Tensiometry after du Noüy

The ring tensiometry is the most frequently used technique to measure the surface tension of pure liquids and solutions. As mentioned above the ring tensiometry is difficult to apply to liquid/liquid interfaces, as it is connected with complicated wetting problems. The same is true for the plate tensiometry, so that complementary techniques are required for these interfaces.

Theoretical basis

In the du Noüy ring method, a thin wire ring is inserted below the interface (which can be either a liquid-vapour or liquid-liquid interface) and held horizontal. Then the ring is pulled up through the interface. The force F measured by a balance goes through a maximum Fmax [[i]]. In a first approximation the surface tension g is given by

[i]. L. du Noüy, J. General Physiol. 1(1919)521

where R is the radius of the ring. Note that for Eq. (V.1) to hold, the radius of the wire must be much smaller than the radius of the ring and that the solution must wet the wire completely. For this reason a clean platinum wire is usually used.

For precise measurements, the use of a correction factor f to the ideal case is required

This correction factor fcorr is a function of the ring geometry and the liquid density r and is included into the software of most tensiometers, such as the TE 2/3. However, it can be also determined by using the tables. For example Harkins and Jordan [[i]] have tabulated the factor as a function of R/r and R3/V, where r is the radius of the wire and V=Fmax/(g Dr) is the volume of the liquid raised above the free surface. Further authors have improved the accuracy of the corrections factors and extended the table also to a wider range of R/r ratios [[ii]]. The table of correction factors given in the Appendix I is taken from [5].

[i]. W.D. Harkins and H.F. Jordan, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 52 (1930) 1751 [ii]. C. Huh C and S.G. Mason, Colloid Polymer Sci., 253(1975)566, 255(1977)460

[i]. W.D. Harkins and H.F. Jordan, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 52 (1930) 1751 [ii]. C. Huh C and S.G. Mason, Colloid Polymer Sci., 253(1975)566, 255(1977)460

Experimental procedure

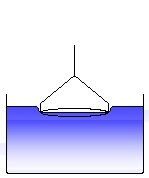

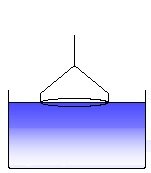

The ring tensiometry is based on pulling a ring out of a liquid and measuring the weight of the attached liquid meniscus.

Principle of the ring tensiometry. The stages of a du Noüy ring experiment for measuring the surface

The ring is outside the liquid and is moved in direction to the surface (or equivalently the liquid container is moved upwards towards the ring). This position is used to determine the zero point of the electronic force balance. (1)

The ring touches the liquid surface. The measured force decreases slightly due to buoyancy of the ring. (2)

The ring has to be wetted by the liquid. A certain force can be necessary to immerse the ring into the liquid, equivalent to the work of wetting. (3)

The ring is immersed into the liquid. This is the starting position of a surface tension experiment. (4)

The ring is moved out of the liquid with a constant speed. (5)

A liquid meniscus is pulled out by the ring. The measured force increases. (6)

The liquid meniscus increases and the force approaches a maximum. (7)

The force passes the maximum and decreases again. The maximum force corresponds to the surface tension of the measured liquid, according to the equation (V.2) given above. (8)

Further pulling the ring leads to a rupture of the meniscus. This process is to be avoided and the software cares about that the ring, after the maximum force has been passed, is moved back into the liquid again. (9)

Fig. V.2 Schematic change of the force measured during the process of a ring tensiometer experiment After the position (4) is re-established, a subsequent measurement can be started. The force measured by the force transducer of the tensiometer changes in the way shown schematically in Fig. V.2. The given numbers refer to the various stages of the experiment. The software controls the ring movement (actually it is the dish containing the liquid that is moved while the ring is in rest) and determines the maximum weight of the formed meniscus.

Effect of contact angle

In contrast to the plate technique discussed below, the effect of the contact angle on the force measurements is of minor importance [[i]]. However, in general a zero contact angle is assumed and the correction factors calculated refer to this value. In particular for thicker wires the effect of contact angle can become remarkable. In some cases, when the contact angle becomes very large, as it may be the case in measurements of cationic surfactant solutions, a measurement is impossible as no meniscus is formed at the ring. In these cases typically the Wilhelmy plate technique fails due to the same reasons and other techniques must be applied, such as the drop shape method [[ii], [iii]].

Effect of adsorption layer expansion

The ring method is similar to the plate method, however it is not truly a static method, as the force measurement is performed while the ring is moving, thus the interfacial area is increasing throughout the measuring process. By performing the process in a slow enough fashion, a good approximation to the equilibrium surface tension can be obtained. However, this is often difficult to achieve, particularly for dilute solutions of highly surface-active material that may require a relatively large time to reach equilibrium. A quantitative analysis has been performed by Lunkenheimer and Wantke [[iv], [v]]. It was impressively shown, that the effect of the surface layer expansion is far larger than the accuracy of the ring tensiometry and can amount to several mN/m. Hence, studies of surfactant solutions, in particular of highly surface active compounds, require special care. Mainly, small dishes for the studied solutions are unsuitable and must be replaced by those of sufficiently large diameter.

[i]. K. Lunkenheimer, J. Colloid Interface Sci., 131(1989)580

[ii]. P. Chen, D.Y. Kwok, R.M. Prokop, O.I. del Rio, S.S. Susnar and A.W. Neumann, in Drops and Bubbles in Interfacial Research, in “Studies of Interface Science”, Vol. 6, D. Möbius and R. Miller (Eds.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1998, pp. 61

[iii]. G. Loglio, P. Pandolfini, R. Miller, A.V. Makievski, F. Ravera, M. Ferrari

and L. Liggieri, Drop and Bubble Shape Analysis as Tool for Dilational Rheology Studies of Interfacial Layers, in “Novel Methods to Study Interfacial Layers”, Studies in Interface Science, Vol. 11, D. Möbius and R. Miller (Eds.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2001, p. 439-484

[iv]. K. Lunkenheimer and K.D. Wantke, Colloid Polymer Sci., 259(1981)354 [v]. K. Lunkenheimer, Tenside Detergents, 19(1982)272

Plate Tensiometry after Wilhelmy

The plate tensiometry, first described in detail by L. Wilhelmy [[i]], is the classical method to determine the surface tension of liquids. This method is a real static technique, i.e. the liquid surface is completely at rest during the measurement.

Theoretical basis

The Wilhelmy plate method involves dipping a thin plate into a liquid and directly measuring the force acting on the plate normal to the interface. The increase in force F measured by the balance is related to the surface tension as follows

[i]. L. Wilhelmy, Ann. Phys. Chem., 29(1863)177

Here w and d are the width and length of the plate, respectively. The contact angle q is usually difficult to measure. The plate is therefore made of glass or platinum, which will be fully wetted (q = 0) if thoroughly cleaned. In that case Eq. (V.3) reduces to simply g = F/P, where P is the circumference of the plate. Surface roughness is often added to the plate to assure complete wetting. Sometimes, mainly in monolayer studies, the plate material is filter paper. Practically, though, contact angle is never measured but assured to be zero. With the use of a modern electro-balance, very precise surface tension measurements can be obtained without the use of any theoretical corrections. This fact, along with the fact that it is a static technique, makes the plate method a popular choice for precise equilibrium surface tension measurements. Note also that commercial versions of this method are readily available. The common disadvantage of this method and the ring method is that a relatively large amount of liquid is needed to perform accurate measurements.

Experimental procedure

Two different approaches can be used, the plate can be left suspended, bridging the two phases, or the plate can be pulled through the interface. The experiments can run for hours. In practice, a wire attached to a balance usually suspends the plate. The solution of interest is raised so that its surface just touches the bottom of the plate. The principle of the plate method is so simple that it can be set up easily in any laboratory equipped with a balance (schematic in Fig. V.3).

Wilhelmy plate in contact with a liquid

Effect of contact angle The measured force depends directly on the contact angle formed by the liquid meniscus and the vertical plate. The force balance reads

When the plate is immersed into the liquid with the length l the measured force is reduced by the buoyancy of the replaced liquid

This relationship is applied when the plate technique is used to determine the contact angle of a solid body available as plate material, which is discussed in detail below.

Contact Angle Methods

There is a number of methods suitable to measure the contact angle of a liquid on a solid body. The most important point in all these methods is that the experimentalist is aware that only equilibrium values can be understood thermodynamically. Moreover, one has to take into consideration, that there are in general two critical contact angles, one receding qr and one advancing angle qa. The difference between the two values is called contact angle hysteresis, which can amount to many degrees, even several tens degrees.

Theoretical Basis

Young’s equation is the basic relationship for calculating the solid surface tension gs from the contact angle q and the surface tension of the liquid gl

As one can see, the equation contains the two parameters q and gl which can readily be measured, and two other parameters gs and gsl which are unknown. Thus, the determination of the solid surface tension gs from Eq. (V.6) requires further information, i.e. an additional relationship between the two unknown parameters gs and gsl. Neumann [[i]] proposed an equation of state of the following form

[i]. A.W. Neumann, Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., 4(1974)105

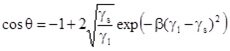

Simultaneous solution of the two Eqs. (V.6) and (V.7) can yield a value of the solid surface tension gs. There are different equations of state proposed in literature. The one proposed by Rayleigh and Good [16] has the following structure

The combination of (V.6) and (V.8) results in an equation for the calculation of the solid surface tension (energy)

This equation seems to work well when both the surface tension of the solid and the liquid are small, while the value of gs becomes too small for liquids with larger surface tensions glv. Good proposed to introduce an interaction parameter F into Eq. (V.8) to account for this deviation [[i]]

[i]. R.J. Good, J. Colloid Interface Sci., 59(1977)398

which finally yields the following relationship

The specification of this parameter F has been tried by many authors. Fowkes’ approach suggests that a surface tension can be decomposed of different components

where gd is the dispersion and gh the polar component. From this ansatz together with Eq. (V.10) Fowkes arrived at the his equation [[i]]

[i]. F.M. Fowkes, Ind. Eng. Chem., (1964)40

which differs from Eq. (V.8) only by using the dispersion part gd of the two tensions instead of the whole tension value. Combined again with (V.6) we obtain

This equation is frequently used for the interpretation of contact angle data to obtain the solid surface tension. A generalisation of the Fowkes approach was proposed by Owens and Wendt [[i]]. The Lifshitz-van-der-Waals /acid-base approach given by van Oss et al. [[ii]] provides more components of the solid surface tension: , and .

[i]. D.K. Owens and R.C. Wendt, J. Appl. Polymer Sci., 13(1969)1741 [ii]. C.J. van Oss, M.K. Chaudhury and R.J. Good, Chem. Rev., 88(1988)927

Another equation of state for the parameter F has been proposed by Li and Neumann [[i]]

[i]. D. Li and A.W. Neumann, J. Colloid Interface Sci., 148(1992)190

The value of b has been determined from a large number of experimental contact angle data and has the values of b=0.0001247 (m/mN)². Together with Young’s equation (V.6) we obtain an implicit relationship for the solid surface tension gs in the following form

For measured values of q and gl the value of gs can be calculated by an iterative method via Eq. (V.16). The following Fig. V.4 demonstrates how the contact angle depends on the surface energy of the solid when a respective pure solvent is used (with hypothetical surface tensions of 70, 50 and 30 mN/m surface tensions, respectively).

Fig. V.4 Change of the contact angle q in dependence of the surface tension of the solid gs for a given liquid of surface tension gl: ¿ - 70 mN/m, ¢ - 50 mN/m, -p 30 mN/m

For example, if we form a drop of water (gl = 70 mN/m at 35°C) an a solid and measure a contact angle of 60 degrees the surface tension of the solid is about 46 mN/m, while when the measured contact angle were 100 degrees, this values would be gs = 20.5 mN/m. For other liquids other dependencies of Q(gl) result, as shown in Fig. V.4.

Plate Technique

In the Wilhelmy plate technique, as mentioned above, the force acting on a plate is measured. This force is determined not only by the surface tension but also by the contact angle. When a plate is now brought into contact with the liquid and immersed into it continuously, and afterwards withdrawn with the same speed, a function of the force in dependence of the length of immersion is obtained as shown in the Fig. V.5. When the plate is immersed a steady contact angle is reached after a certain distance, which refers to the advancing contact angle. When the plate is withdrawn, the receding contact is obtained after a certain transient period. The forces extrapolated to zero immersion depth l=0 are Fa and Fr, respectively, with and . From these two values the respective contact angles can be calculated easily. As solid surface are energetically not homogeneous, there is a certain scattering in the curves so that the two values Fa and Fr have to be determined by linear regression and extrapolation to I=0.

Fig. V.5 Schematic of a force versus immersion depth dependency F(l)

Sessile Drop Technique

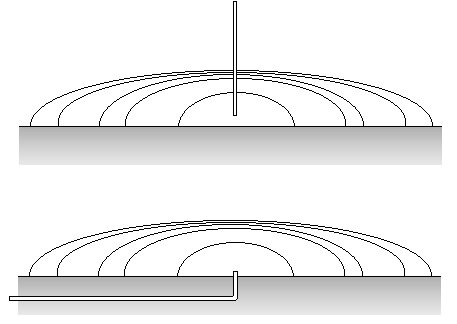

This method is based on the determination of the shape of a drop sitting on the solid under study. In order to measure the receding and advancing contact angles, again the liquid has to move over the solid surface. This is arranged in different instruments either via a capillary from underneath or from the top, as schematically shown in Fig. V.6.

Fig. V.6 Sessile drop with growing volume; liquid delivered via a thin capillary from top or bottom, respectively

This method is possibly superior to the plate technique, however, it requires an expensive instrumentation, including video and computer technique, and accurate mechanical parts. The advantage is the small amount of liquid and the applicability to quite a large number of systems, such as molten polymers or alloys. Commercial instruments are available from different producers, including pressure and temperature cells.

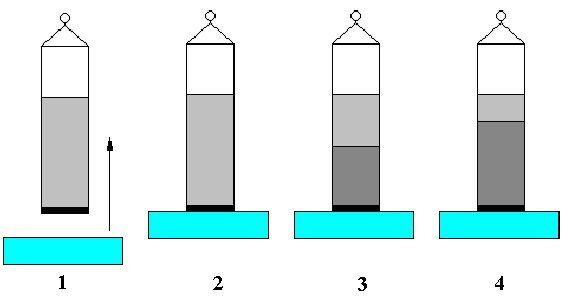

Washburn Method

This method allows to measure the contact angle of disperse particles such as powders or fibres. A glass tube is filled with the material and closed with a porous lid. The filling procedure is extremely important to obtain reproducible results and depends on the material. The measurement is an automated procedure in the software of the TE 2/3. The principle steps of the experiment are shown in Fig. V.7. First the filled tube is hooked to the balance (1) and then brought into contact with the liquid (2). The liquid starts to wet the powder, hence the liquid meniscus rises inside the tube. After a transition period (3) a constant rising speed is reached, which later levels off and terminates (4). Fig. V.8 shows schematically the result of an experiment.

Fig. V.7 Principle of the Washburn method to determine the contact angle of a powder

Fig. V.8 Schematic of the function force F versus time

The Washburn equation which describes the experiment reads

The parameters in Eq. (V.17) are: r - density difference between liquid and air, h - viscosity of the liquid, g - surface tension of the liquid. The coefficient K stands for the porosity of the powder in the tube and has to be determined separately. Traditionally it is determined by a separate experiment using a liquid that wets the particles perfectly, for example hexane. Then the porosity coefficient k results to

as the contact angle can be assumed to be zero. This technique is easy to handle, however, reproducible results require a lot of experience in particular with respect to the preparation of the tube packing, as any changes in the porosity coefficient influences the measured contact angle directly. When experiments with other liquids are performed the advancing contact angle can be obtained from the equation

Experimental Results

top

top

Maximum Bubble Pressure

top

Profile Analysis

top

Capillary Pressure

top

Drop Volume

top